Eye For Film >> Movies >> Amanda Knox (2016) Film Review

Amanda Knox

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

On the 1st of November 2007, just two months short of her 22nd birthday, Meredith Kercher was violently assaulted and murdered in the flat she was renting in Perugia, Italy. Mez, as she was known to friends, was a student who dreamed of becoming a journalist or working for the EU; whilst she studied, she was travelling and working as a tour guide. You won't learn any of that from this film, however, because Kercher is barely mentioned except to speculate about the details of her death. The focus of the film, as of the media at the time, is one of the accused, the titular Amanda Knox.

Why Amanda Knox? Murders happen all the time. Although only 4% are committed by women, that still accounts for nearly 20,000 cases in the year in question. But the sexually motivated murder of an attractive young white woman, a Londoner, with one of the accused being an attractive young American woman, with extreme violence involved and an element of mystery - that's the kind of thing that gets noticed. When women like Knox are suspected of murder, society reacts in a way out of all proportion to the way it treats male murderers - 35 years after the Moors murders, 20 undertakers reportedly refused to cremate the body of Myra Hindley, but male killers often fail to make the national news even for a day. Knox, in an extensive interview that forms the backbone of this documentary, shows an acute awareness of this. guilty or innocent, she is a victim of prejudice at numerous levels - and, ironically, that prejudice could have weakened the case against her.

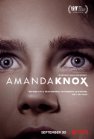

People think they can see it in her eyes, Knox says, but that's not objective evidence. Nevertheless, viewers will find themselves searching. Knox moves those eyes in ways which, if one studies the literature on body language, are distinctly incriminating - but she's odd, she says, she knows that, she's always been odd; and research into these things can only deal in generalities. Some of her behaviour is narcissistic, even callous, but that's no indicator of guilt. A recorded phone call made just days after the murder features her mother telling her that this could be the best year of her life, despite the fact that her friend has just been killed. One wonders what habits she picked up at home, ad how they might have made her look to a succession of juries.

Others interviewed in this documentary are wholly convinced of Knox's guilt or innocence (something she insists is true of everyone). Prosecutor Giuliano Mignini speaks passionately of his certainty about her guilt from the early stages of the investigation. Both she and co-accused Raffaele Sollecito seem bamboozled by questioning techniques obviously designed to rattle them and try to prompt slips. It's not clear if either had a lawyer in the early stages. Sollecito is sentimental, more sympathetic than in previous interviews, lamenting the ongoing romance he might have had with Knox, yet it's notable that he too is very much focused on his own tragedy, speaking of Kercher only in passing.

As we follow the detailed process of the investigation, the appeal, and the later trials, the film goes into detail about the evidence, bringing in forensics experts and doing a good job of explaining their work in layman's terms. There are still some curious anomalies that don't seem to prompt enough questions - a locked bedroom door, a covered body, the alleged removal of the murder weapon to Sollecito's house (if moving it, why not just throw it in the sea?) Knox's behaviour prior to discovering the body is definitely odd - finding her front door open but apparently not looking for her flatmate, wandering around the apartment without noticing the smell of blood. Yet speculation about what might have happened is complicated by cultural and generational differences. Fanciful notions about Kercher and Knox's morality lead to the creation of complex narratives where much simpler ones might suffice. With distraction abounding, the investigators seem to move further and further from their goal, yet the filmmakers themselves are alert to this.

Interwoven with this narrative are contributions from Daily Mail journalist Nick Pisa, who sums up media concerns at the time with cheery amorality almost as chilling as the murder. The only thing that could have made it better, he says, would be if the pope or a member of the royal family were involved; and he talks about the great photos he found on social media with a complete disregard for the copyright law that might have protected their subjects from misrepresentation.

There's repetition of the old argument that everything is justified by public demand. It's hard to know how much that demand stems from habit or education. Why do people want to see this film? Some effort has been made to avoid sensationalism; there is, for instance, no detailing of Knox's past lovers here, though the fact that this appeared in the newspapers is mentioned. Directors Rod Blackhurst and Brian McGinn do a good job of keeping things balanced and of illustrating the ways in which sensationalism can be misleading. The mystery remains. In the end, all we can see is fragments. The man doing time for Kercher's murder, Rudy Guede, who has curiously maintained his innocence even after exhausting the appeals process, says she tried to tell him something before she died. But now she is silent.

Reviewed on: 21 Dec 2016